Frequently Asked Questions

Nature Medicine (Sep 5, 2022)

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02000-0

Lingering PostCOVID cardiac symptoms relate to cardiac inflammatory involvement in previously well people with mild initial disease |

A total of 73% of patients reported cardiac symptoms at baseline, whereas 57% continued to experience symptoms at follow-up. We report mild but persistent non-ischaemic cardiac inflammation, which was not associated with overt structural heart disease or significant troponin release. Although these observations were triggered by a viral infection, a profound myocardial injury or functional impairment was not a characteristic of post-acute COVID cardiac involvement, contrary to the classical definition of viral myocarditis. Its pathophysiology seems to be more reminiscent of the findings in other chronic diffuse inflammatory syndromes that occur in chronic post-viral syndromes or autoimmune conditions. The long-term prognostic relevance of post-acute COVID cardiac involvement in previously healthy people with mild initial COVID illness requires further investigation.

A few limitations apply to this study. These results are based on a selected population of individuals who recovered from COVID-19 infection and where the symptoms were commonly the motivation to take part, thus extrapolation of the prevalence of symptoms or findings onto the general population is not possible. Although mapping techniques provide valuable pathophysiological insights, the transferability of these findings is limited by a lack of standardization and methodological variations among the vendors and expert centres. Although most likely driven by an autoimmune process, the underlying pathophysiology remains only partially understood.

This study is unique in following the evolution of changes from the onset of disease. The authors would like to thank all study participants and staff of the Institute for their dedicated support of this study. This research was enabled with support from Bayer AG, the German Heart Foundation and German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK).

A few limitations apply to this study. These results are based on a selected population of individuals who recovered from COVID-19 infection and where the symptoms were commonly the motivation to take part, thus extrapolation of the prevalence of symptoms or findings onto the general population is not possible. Although mapping techniques provide valuable pathophysiological insights, the transferability of these findings is limited by a lack of standardization and methodological variations among the vendors and expert centres. Although most likely driven by an autoimmune process, the underlying pathophysiology remains only partially understood.

This study is unique in following the evolution of changes from the onset of disease. The authors would like to thank all study participants and staff of the Institute for their dedicated support of this study. This research was enabled with support from Bayer AG, the German Heart Foundation and German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK).

Main Messages

- There is a considerable ongoing cardiac inflammatory involvement in the heart muscle weeks-months after the recovery from the acute COVID19 illness. This finding is important because it may cause future heart damage and may herald a considerable burden of heart failure in a few years from now.

- Early diagnosis is important because there is a good chance that early treatment could reduce the relentless course of inflammatory damage or even halt it. To prove this, we need clinical trials most urgently.

- It matters to use cardiac MRI as the diagnostic test of choice because it is very sensitive to detect tissue changes directly with the heart muscle. However, we need standardised and validated cardiac MRI platforms, which are not available routinely. Different vendors and expert centres use many different techniques, which yield different results. This makes the findings not transferrable.

- We believe that cardiac MRI scans must be humane and designed to deliver the relevant clinical information within the shortest amount of scanning time (short -> 20 min).

- There must be more efforts made to make MRI machines available for cardiac indications because it prognostically matters most what happens with the heart.

- We need to give the heart time to heal, even if there is a paucity of symptoms. We recommend avoiding any sports for 4 weeks, and slow return to moderate exercise in subsequent months, even if you have no symptoms at all. In those with symptoms, we advise guiding patients with CMR evidence of ongoing inflammation. Neither normal echo nor an absent troponin can exclude PostCOVID heart involvement.

|

In the video below, Dr Puntmann explains the typical findings in the heart in a young patient with Long COVID symptoms.

|

|

|

Why are the findings important?Cardiac involvement may not be the most visible part of the acute illness, however, it is detectable in a considerable proportion of patients a few weeks later. We now report that in patients with symptoms cardiac inflammatory involvement can persist for many months. Some patients may have mildly reduced pumping function, however, overt structural heart disease or severely impaired pumping function is not characteristic, and is more likely related to pre-existing heart disease. While we do not yet have any direct evidence for any late consequences yet, it is possible that in a few years, the burden of PostCOVID related heart disease will be considerable.

|

Cardiac Symptoms and Long COVIDPatients with long COVID often develop symptoms that relate to cardiac involvement, including resting or excessive tachycardia (POTS-like presentations), and shortness of breath, especially when attempting the inclines. Exercise or effort intolerance is also very common. These two reflect stiffer heart muscle due to the effects of PostCOVID inflammation. Patients also report burning chest pains or deep chest discomfort, often migrating towards the back or getting worse on inspiration. These symptoms relate to the inflammation of the heart's lining, the pericarditis. Deep chest tightness after exercise or at the end of a busy day, relates to small vessel involvement.

|

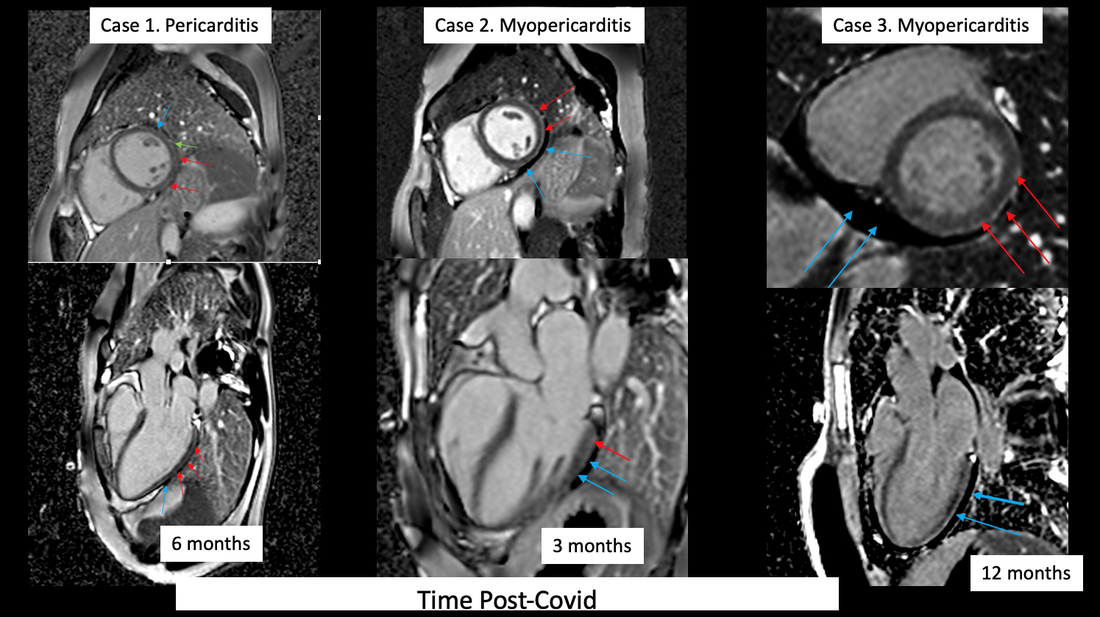

Late gadolinium enhancement images of 3 cases with cardiac PostCOVID symptoms. Blue arrows-> pericardial effusion; red arrows - non-ischaemic myocardial enhancement.

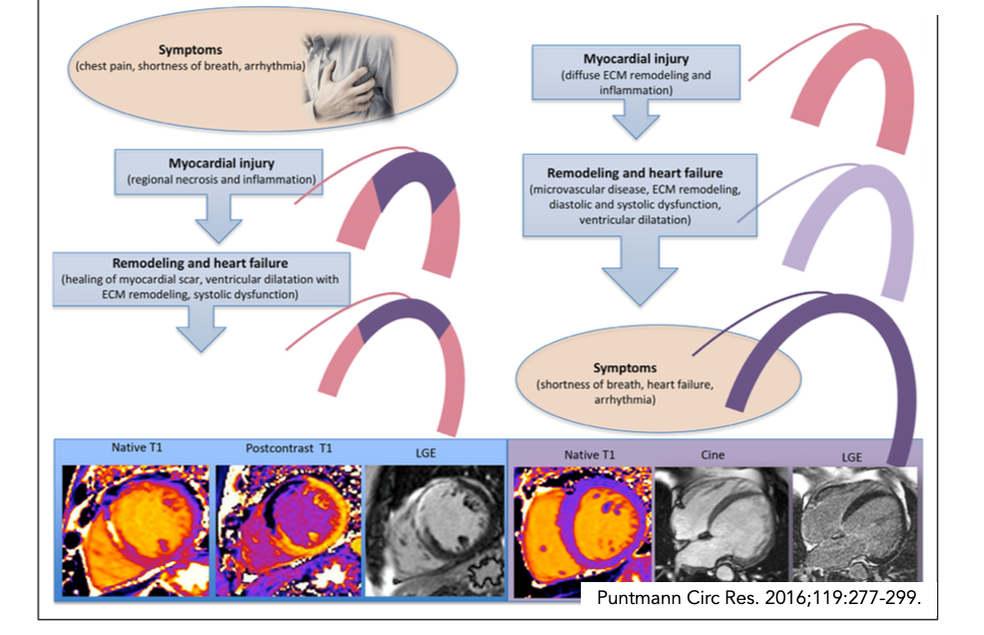

Understanding heart inflammationHeart doctors often assume that myocarditis is a very severe disease and expect it to present either with severe symptoms of heart failure or cardiogenic shock or at a minimum structural heart disease (dilated cavities, impaired pumping function, significant troponin release). This is true for the infarct-like form of viral myocarditis with considerable areas of necrosis, but not accurate for all forms of myocardial inflammation. In fact, most patients have much milder versions of myocardial inflammation and not much in a way of typical heart-specific symptoms in myocarditis.

It is also widely assumed that most patients heal swiftly without residual heart damage. Yet, our serial observations in classical viral myocarditis patients reveal that the healing process takes several months or years. Often, there is a silent or subclinical (ie. under the threshold of our current classification of cardiac symptoms) ongoing myocardial inflammation and build-up of diffuse fibrosis. The areas of necrosis noted in the acute stages tend to heal with a residual scar. In some patients, heart cavities may dilate and pumping will be less strong (reduced LV Ejection Fraction), whereas others may develop shrunken and stiff hearts (with preserved Ejection Fraction). Eventually, these structural changes of the heart give way to symptoms, such as reduced fitness (exercise intolerance) or shortness of breath on exertion. Is there an active virus infection of the heart myocardium?In our biopsies, we found no evidence of viral particles actively replicating. This is consistent with several reports in the literature. This means that whereas the infection likely acts as the initial trigger, PostCOVID cardiac inflammatory involvement is due to autoimmune mechanisms and not an active viral infection. There is also no evidence that the virus damages cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells) directly. Virus particles have been demonstrated only in a paucity of patients that died during the acute disease, however, they were found in inflammatory cells coming into the heart from elsewhere.

Do we need early diagnosis?Early diagnosis is important because there is a good chance that early treatment could reduce the relentless course of inflammatory damage or even halt it. However, myocardial inflammation - as also shown in our patients - is prevalently a silent pathology (i.e. subclinical). The heart problem presents with atypical symptoms, niggling chest discomfort or deteriorating fitness in a young person. Early diagnosis helps to find out whether patients are recovering properly, guide the level of sports activity and guide therapy (see below).

|

Which test for cardiac inflammationGiven the subclinical course and evolution, the severity of this condition cannot be judged based on the symptoms. Thus, establishing an accurate way to objectify heart involvement is invaluable. However, it matters profoundly how to go about this. One way to detect cardiac damage is a troponin test. However, troponin is a test to diagnose acute complications of coronary artery disease such as a 'heart attack’. The established cut-off values have been trained on the population of patients with a suspected heart attack. It has never been validated for use in myocardial inflammation, meaning, the current cut-off values cannot be used to detect or exclude myocarditis. Similarly, echocardiography, although widely available, is not a sensitive test for myocardial inflammation, because it simply cannot see inside the heart muscle tissue. In myocardial inflammation, the pumping function remains normal for a long time (as also shown in our patients). We perform echo in parallel to cardiac MRI in all of our patients, so we know that there is a huge diagnostic gap between echo and MRI. Finally, in some countries, doctors would only rely on heart biopsies to confirm heart inflammation. Heart biopsy is an invasive test, performed in a catheter lab. It is expensive, not widely available, not standardised (no clear cut-offs that relate to prognosis) and, relies on the presence of necrosis to be positive (Dallas Criteria). Also, it is not without complications. The evidence that biopsies help to improve treatment is also missing. Heart biopsies cannot be rolled out as a scalable test for everyone. Cardiac magnetic resonance is the diagnostic test of choice for inflammatory cardiomyopathies, as it is very sensitive to detect changes such as increased water content or fibrosis directly within the heart tissue.

High prevalence of cardiac involvementEver since the first reports suggesting autoimmune mechanisms, we believed that the heart would have also been involved, because cardiac inflammation is essentially an autoimmune condition. The high prevalence of inflammation is in part due to the patient population that sought help due to symptoms, as well as the very sensitive imaging methods which we use for many years, and which are not available routinely. These methods are standardised and validated to detect diffuse inflammation and fibrosis, explaining the higher capture in our studies compared to other centres. We also use Gadovist as the contrast agent of choice due to high contrast at a low dose.

Importantly, we do not use Lake Louise Criteria to characterise our imaging findings due to their limitations in relying on necrosis, and low sensitivity for detecting diffuse heart disease. |

Are there any postCOVID therapies?

Currently, there is not a lot of evidence for any treatment of long COVID symptoms. The usual guideline-directed heart failure therapy can be initiated in those with reduced ejection fraction. For those with pericarditis, low-dose colchicine treatment for 4-6 months can help. In those with severe resting tachycardia, beta-blockers and ivabradine can offer some relief. Doctors may not be very experienced at taking proactive therapeutic action prior to the development of heart failure symptoms (also known as cardio-protection). Many would also not know that cardiac MRI can help with that. A considerable proportion may also not have easy access to cardiac MRI, and even fewer will have the training to make good use of CMR findings. We are working hard to change this so that the patients can finally benefit from the deeper insights offered by CMR.

In clinical trials, we test an existing or novel medication in a randomised double-blind (placebo-controlled) study. This means that some patients may receive treatment and some will not, however, neither patient nor doctor will know. At the Institute of Experimental and Translational Cardiovascular Imaging, we are in the process of initiating a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial of cardioprotective treatment (MYOFLAME-19) in previously well people with recent COVID Infection and heart symptoms (shortness of breath on exertion, chest pain, tachycardia). If interested, please read more.

Further Reading

Further Reading on PostCOVID Cardiac Involvement:

https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109799000480

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.CIR.98.17.1742

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002914906007260

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-02000-0#citeas

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.08.09.22278592v1.article-info

https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109799000480

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.CIR.98.17.1742

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002914906007260

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-02000-0#citeas

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.08.09.22278592v1.article-info